A drizzle of sweet and salty caramel sauce over a slice of pie can be just the thing to take it to the next level. This salted caramel sauce recipe has a rich, buttery sweetness that’s balanced with just the right amount of salt. Try it drizzled over a slice of brownie pie with a scoop of ice cream, or use it in my caramel apple pie filling. Beyond pies, it’s just as delicious spooned over cheesecake, drizzled on pancakes, blended into milkshakes, or even stirred into your morning coffee.

Table of Contents

The Science of Caramel Sauce

What is Caramelization?

At its core, caramel is simply sugar that has caramelized. In other words, sugar that has been heated until the sugar molecules break down and transform (a much nicer word than “burnt”). A basic, hard caramel is made with one ingredient: sugar. The flavor profile depends almost entirely on how long you let the sugar cook and how much you let the color darken. The lighter the caramel, the milder and sweeter the flavor. The darker the caramel, the deeper, more complex, and slightly more bitter the taste becomes.

The key to a great caramel is stopping the caramelization process at just the right point. Remove it from the heat too soon, and you won’t get much caramel flavor. Too late, and the caramel will take on more of a “burnt” flavor. The trick is to find the sweet spot (literally) where the flavor is bold but not yet harsh.

If you’ve read my post on how to make the perfect pie dough, you might remember that we talked about the Maillard reaction. Caramelization is like its fraternal twin. Both are browning reactions triggered by heat, but they affect different molecules. The Maillard reaction transforms proteins (like those found in flour, meat, or dairy), while caramelization transforms sugars.

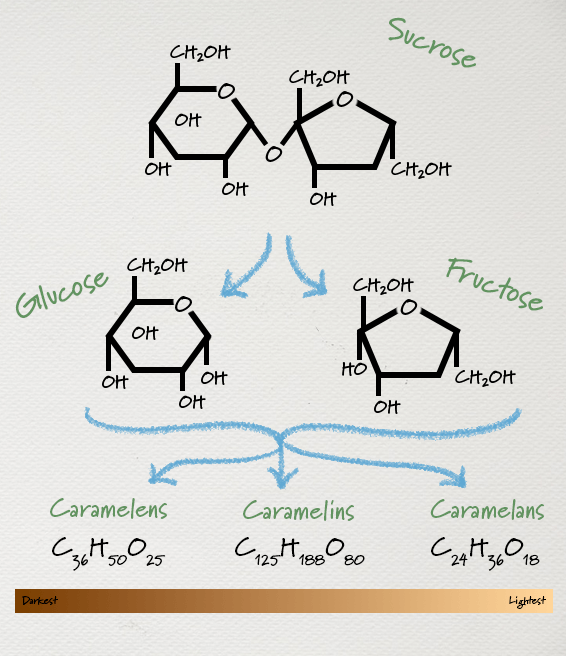

As sugar molecules reach around 338°F (170°C), they begin to break apart and recombine, forming new compounds called caramelans, caramelens, and caramelins. These polymers are what give caramel its signature golden color, complex aroma, and layered flavors. If you’re a total science nerd and you’re interested in the chemistry behind caramel, this paper dives into some of the nitty gritty food science.

Wet Caramelization vs Dry Caramelization

There are two main methods of caramelization: wet and dry. Each has its own pros and cons. In this salted caramel sauce recipe, I use the wet caramelization method because I feel it gives you more control, but you can absolutely make this recipe with the dry caramelization method if you prefer – just omit the water and corn syrup.

Dry Caramelization:

Dry caramelization is the more traditional, minimalist approach. You simply add plain, granulated sugar directly to a pot, and let it melt and caramelize without any added liquid.

Because there is no water to boil off first, the sugar reaches caramelization temperature much more quickly. The speed is both a benefit and a challenge: the process moves quickly, leaving little room for error. It’s easy to overshoot and end up with burnt caramel.

For experienced cooks, the dry caramelization method might be the method of choice when you want a deep caramel flavor quickly. It can be trickier to master than wet caramelization though.

Wet Caramelization:

Wet caramelization slows things down, making the process a bit more forgiving. With wet caramelization, the sugar is first dissolved in water before being brought to a boil.

Because sugar doesn’t begin to caramelize until about 338°F (170°C), and water boils at 212°F (100°C), the presence of some water slows down the speed at which the sugar reaches the point of caramelization significantly. This extra time can give you more margin for error and control over the final color of your caramel.

A common misconception is that adding water will make the finished caramel more watery. In reality, by the time the caramelization process begins, all the water has boiled away. What’s left is pure, melted sugar ready to transform into caramel. (If you add water after caramelization has occurred, however, you’ll dissolve and dilute your caramel).

Why add butter and cream to caramel?

Adding butter and cream is what transforms your caramel from a hard candy into a smooth, rich, pourable salted caramel sauce. The butter provides richness, flavor, and a smooth texture, while heavy whipping cream emulsifies the mixture and keeps the caramel soft and glossy as it cools.

For best results, heat your cream to a scalding temperature before adding it to your caramel. Pouring cold cream straight from the refrigerator into your hot caramel can cause thermal shock, making the caramel seize into one hard clump.

The order of operations matters too. Always remove the caramel from the heat before adding either the cream or the butter. Then, add the cream first, followed by the butter. Butter is a delicate emulsifier, and if it gets too hot, it can break, leaving your sauce feeling greasy instead of rich and smooth. Adding it last after the cream has already emulsified the sauce helps it blend seamlessly with the caramel.

Finally, add the cream just a little at a time. It will immediately bubble and rise when it hits the molten sugar. Adding just a little at a time prevents the mixture from boiling over and creating a hot, sticky, hard to clean mess on your stove. You don’t need to stir while pouring the cream in. Wait until it’s all been added, then whisk everything together once there’s no risk of hot splatter.

Troubleshooting Caramel:

My caramel keeps burning: If you’re using the dry caramelization method, switch to the wet caramelization method. This gives you much more control over the speed at which the caramel begins to burn. Use low heat and watch carefully as soon as the sugar begins changing color.

I’m getting sugar crystals in my caramel: If you notice your caramel begin to turn grainy, or you notice white crust bits forming on the surface and sides of the pot, you’re dealing with sugar recrystallization. This happens when the sucrose molecules in white sugar start to reform into crystals instead of staying dissolved.

If it’s only happening a little bit, don’t worry. The crystallized sugar will dissolve back into the sauce when adding the cream. However, there are a few easy additions you can use to reduce the likelihood of recrystallization.

- Adding a little corn syrup

- Corn syrup is made from glucose and fructose, while granulated sugar is sucrose. They taste similar, but the different molecules interfere with each other. The glucose and fructose in the corn syrup act as “disruptors”, preventing the sucrose molecules from linking up and forming crystals.

- Adding abit of lemon juice

- Lemon juice contains citric acid, which breaks down some of the sucrose in granulated sugar into glucose and fructose. Like with the corn syrup, these molecules disrupt crystallization to help keep your caramel smooth.

In this salted caramel sauce recipe, I use ½ tablespoon of corn syrup to reduce the crystallization.

My caramel seized and became grainy: If you’re using the dry caramelization method, it’s not uncommon for the sugar to seize up and become grainy and clumpy. This usually happens because the sugar was stirred while caramelizing. To fix the problem, add a few tablespoons of water and stir until the sugar dissolves again. At this point you’ve essentially converted the process into the wet caramelization method.

I added the cream and my caramel seized into a hard lump: Make sure your cream is warm, even bringing it to just under a boil, before adding it to your caramel. If you add cold cream to the extremely hot, molten sugar, your caramel will experience thermal shock and seize. If it does seize, heat the mixture over low heat until it melts again. Add a little more (warm) cream to re-emulsify it if necessary.

Step-by-Step Salted Caramel Sauce Recipe:

Ingredients

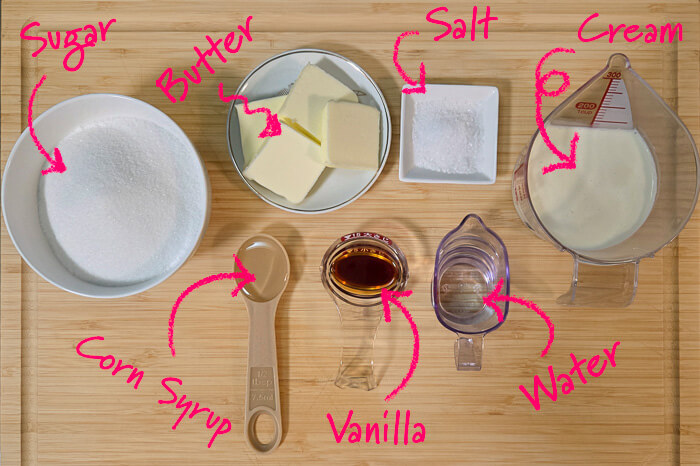

- 1 cup (200g) granulated sugar

- 2T water

- ½T light corn syrup

- 1/4c (½ stick) unsalted butter

- 1/2c heavy whipping cream

- 1/2T vanilla extract

- 1t salt

1.

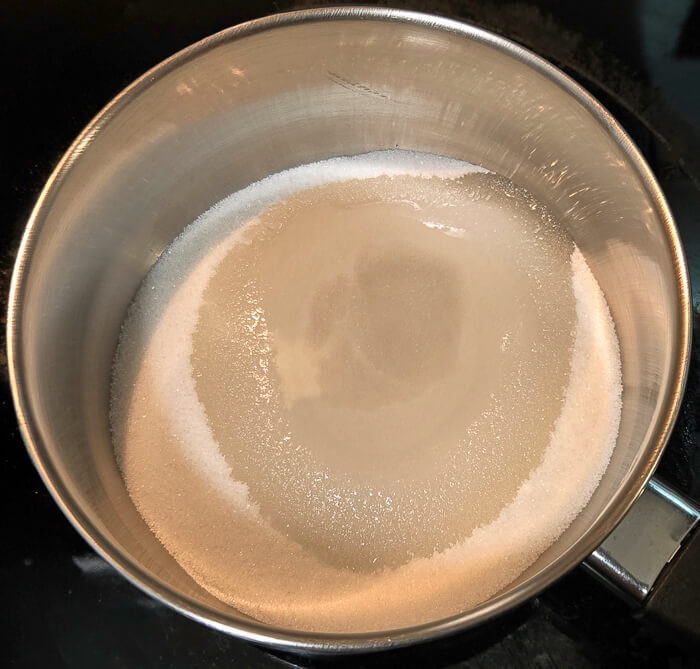

In a pot on medium heat, combine the water, sugar, and light corn syrup. Bring to a boil, and do not stir.

In a pot on medium heat, combine the water, sugar, and light corn syrup. Bring to a boil, and do not stir.

2.

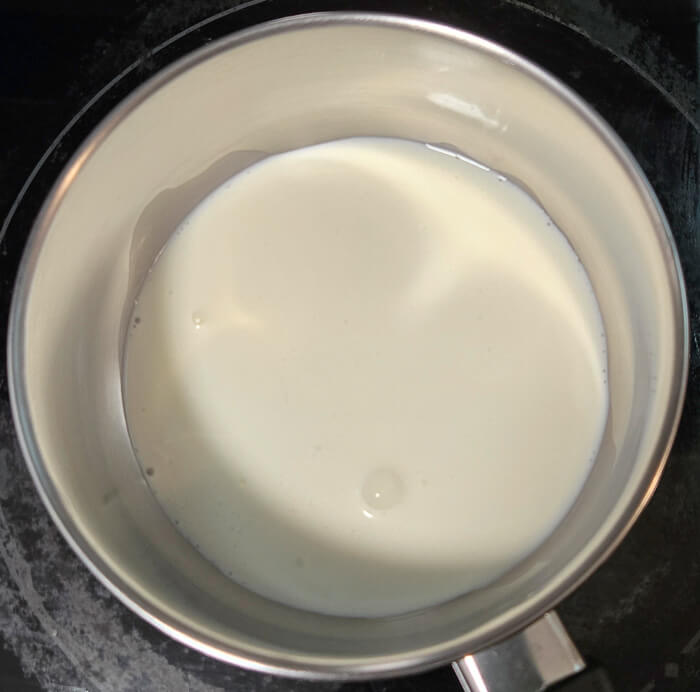

In a separate pot, heat your heavy whipping cream until it’s just about to boil.

3.

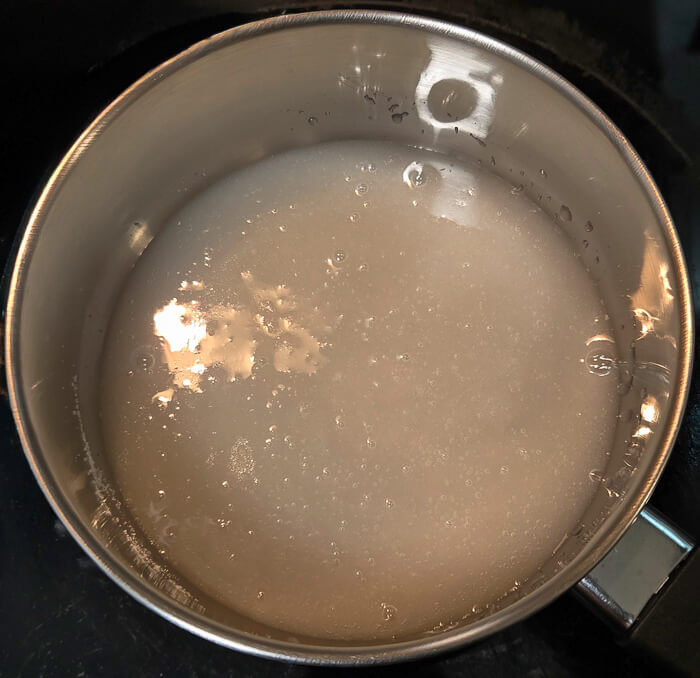

Once your sugar mixture begins boiling, without stirring, watch your sugar carefully for it to begin browning. As soon as it reaches your desired level of caramelization, take the pot off the heat.

4.

After removing your caramel from the heat, stir constantly while slowly pouring the hot cream into the caramel.

This can cause lots of splattering, so wear gloves while doing this step.

5.

Once the cream is fully incorporated, whisk in your butter, salt, and vanilla.

How to Use Salted Caramel Sauce:

- Drizzle over desserts: Pour it over pies, cakes, cheesecakes, or a scoop of ice cream. It’s especially delicious on brownie pie.

- In baking recipes: Swirl it into bars, brownies, or pies for an extra layer of flavor. This caramel sauce is used in my caramel apple pie recipe.

- In drinks: Stir into lattes, hot chocolate, or even milkshakes for a sweet, salty kick.

Salted Caramel Sauce

Ingredients

- 1 cup Granulated Sugar (200g)

- 2 tbsp Water (30mL)

- ½ tbsp Light Corn Syrup (8mL)

- 4 tbsp Unsalted Butter, cubed (½ stick)

- ½ cup Heavy Whipping Cream (120mL)

- ½ tbsp Vanilla Extract (8mL)

- 1 tsp Salt (5g)

Instructions

- In a pot over medium heat, combine water, sugar, and corn syrup. Whisk together once and then bring to a boil. Do not whisk it again until step 4.

- In a microwave safe container or another pot, heat the cream until it is just below boiling temperature.

- Watch the sugar mixture closely. When it turns your desired level of golden brown, immediately remove it from the heat.

- Wearing gloves to avoid burns from splattering, pour the cream into the caramel, a couple tablespoons at a time.

- Once all the cream has been added, whisk the mixture together.

- Whisk in the butter, salt, and vanilla until smooth.

One Comment

Easiest recipe to make and so delicious. Thank you!